Dealing with dead stock can be a daunting issue for any retail business, posing significant financial burdens and logistical headaches....

Type above and press Enter to search. Press Esc to cancel.

News you care about. Tips you can use.

News you care about.

Everything your business needs to grow, delivered straight to your inbox.

Featured post

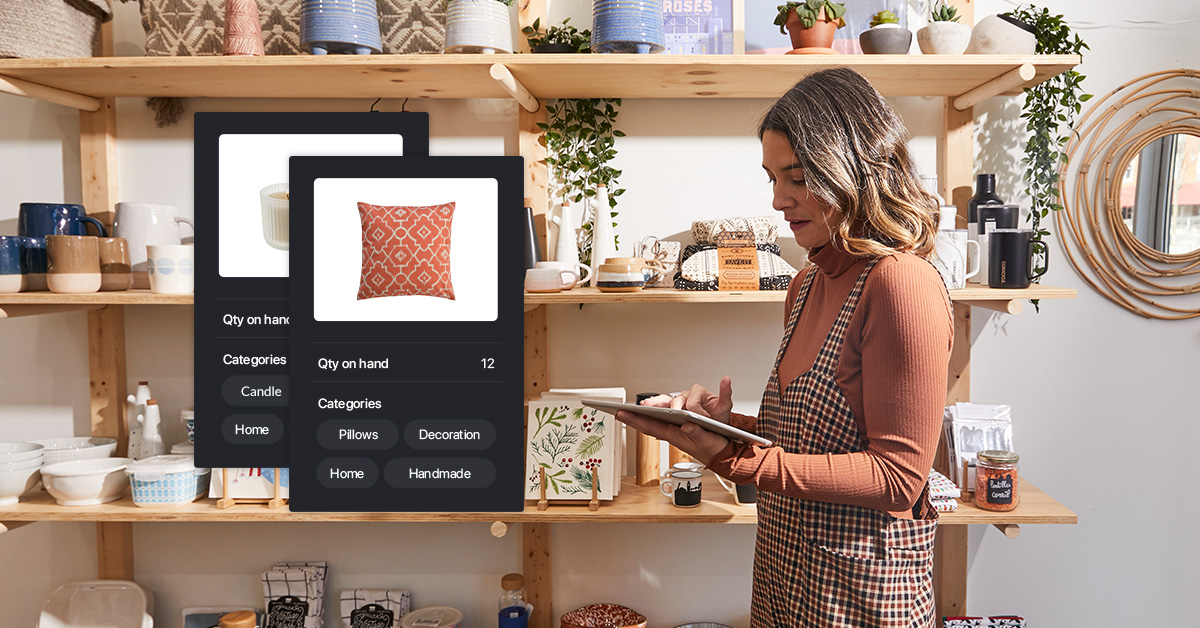

When you run a store, it’s critical to keep a finger on the pulse of your business. Paying attention to metrics like inventory value...

Most read articles

Opening a coffee shop isn’t easy, but a detailed coffee shop equipment list can set you up for success. According to a July 2020...

When you start a retail business, one of the first things to figure out is where you’re going to find products to sell. This might...

You’re taking the plunge: opening your own online store. You know which products you want to sell. And you know who your target market...

With the recent and unforeseen increase in the popularity of golf, operators are no longer fighting to attract players to their facilities....

Recent articles

Marketing your business can take up a ton of time and resources. As a retailer, it can be difficult to gain traction through your marketing...

Unless you’ve been doing business under a rock lately, then you know that Mother’s Day is only a few weeks away. And while it isn’t...

Who do you think of when someone says the words “famous chef”? Everyone has a favorite chef/TV personality, and it’s rarely based...

Picture this: you’re out shopping, and you have time for one more stop. There are two stores in front of you. One hasn’t put much...

It’s finally here: April through September is the season for golf major championships. This concentrated window of time is when the...

Tired of being shouted at? We’d imagine you’ve experienced this once or twice if you’ve had to deal with a difficult customer....

Restaurant labor costs are one of the highest costs of owning a restaurant. However, a full-service, white-tablecloth restaurant will...

Well drinks are alcoholic drinks that rarely show up on drink menus but are still ordered every day in bars and restaurants across...

Choosing an aesthetic for your business can be overwhelming, and with so many restaurant design and decor ideas out there, it’s hard...

So you’re thinking of opening a cafe. We salute you. A well-crafted cafe is a bedrock of your community, a welcome stop in any big...

Being a pro retailer means more than knowing how to sell the right products to the right customers. You need to be an expert in inventory...

Give me one margarita, I’ma open the restaurant doorGive me two margaritas, I’ma send my servers to the floorGive me three margaritas,...

Business success is impossible without a good plan. And in the case of retail stores, that means putting in the time and effort on...

Until recently, sustainability was a niche approach in retail. But in the past few years, we’ve seen corporations take on Corporate...

Starting a retail store or boutique—and ensuring that it succeeds—is a major undertaking. One of the biggest factors is the cost. You’ll...

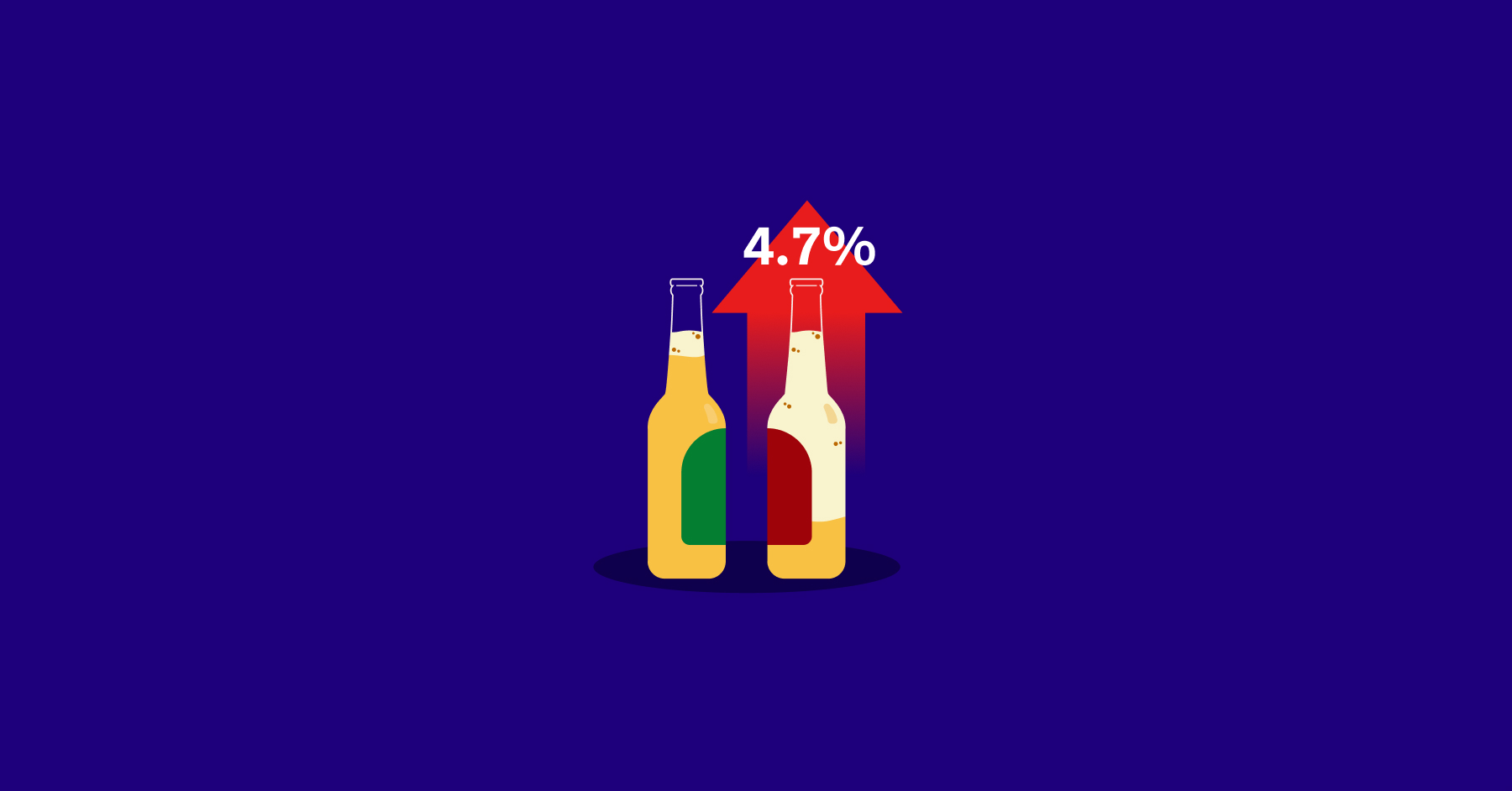

Editor’s note: On March 16, 2024, Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland announced that the 2% cap on the annual alcohol excise tax...

Barcodes are an essential part of doing business as a retailer. So are SKUs. They can feel like second nature, a quintessentially understood...

This article was co-authored by Christian Mouysset, co-founder of Tenzo.According to the United Nations, 17% of the world’s total...

Boutiques are the heart and soul of the retail world. Independent shops never miss a beat when it comes to keeping up with trends,...

For a golf manager, golf facility management is like on-course management. In both instances, you must execute against a daunting array...

Browse more topics

News you care about. Tips you can use.

News you care about.

Everything your business needs to grow, delivered straight to your inbox.